“We’re three caballeros,

three gay caballeros,

they say we are birds of a feather!”

Both Walt Disney and his brother Roy were later to describe the World War II years as the creative nadir of Disney animation. Several Disney artists either volunteered or were drafted into the war effort, leaving the studio short on talent, and a series of separate financial disasters—some related to the war, some not—had left Disney completely broke. Wartime realities shuttered movie theatres abroad, cutting any potential box office revenue. The United States Army moved into the new studio that Walt Disney had so proudly built.

Disney was left making various war training films, a few cartoon shorts sponsored by various branches of the United States government, and a propaganda film, Victory Through Air Power, that left its coffers even more drained. The remaining artists felt stifled. Roy Disney was later to describe the period to Disney historian Bob Thomas as “lost years.”

In the midst of this, Disney had one—exactly one—bright spot: Saludos Amigos had not only earned back its costs in North America, but, to the surprise of everyone, had been popular enough in South America to turn a small profit and keep the doors open. Critical reaction had been mixed, but movie theatres in South America, at least, were still open—and audiences there liked Donald Duck. Plus, Disney still had some unused art from Saludos Amigos—an incomplete cartoon short about a flying donkey, some paintings inspired by Brazil, some silly drawings of birds—that could be used. Perhaps another film using some of the same money saving methods—combining shorter, cheaper cartoons, with simplistic backgrounds and limited special effects and some live action work—might work. Especially if the film focused on Donald Duck.

And as a bonus, Disney could, for the first time since a brief moment in Fantasia and the Alice film shorts, not just have a film that alternated between live action and animation (as in portions of Fantasia and Saludos Amigos), but a film that combined live action and animation—in a technological leap that might even bring war weary North American audiences into the theatre. At the very least, it could provide a few Donald Duck moments to send over as part of the entertainment for World War II soldiers. Walt ordered the film into production, but it’s safe to say that neither he, nor anyone else, envisioned what Disney artists, apparently desperate to escape from any semblance of reality whatsoever, would create as a result: the single weirdest film ever to escape the Disney studio.

Oh, The Three Caballeros starts off more or less normally. Against a simple, cost saving background (the first of many cost saving techniques used in the film), Donald Duck receives a birthday present from the South American friends he met in Saludos Amigos, presumably parrot José Carioca and the llama, although the llama does not appear in this film. It’s a splendid present that makes me instantly jealous: a movie projector plus cartoons: The Cold Blooded Penguin, The Flying Gauchito, and some silly stuff with birds, starring the Aracuan Bird. Nobody ever gives me presents like that. Anyway, Donald squawks happily and immediately sits down to watch the cartoons—a task that involves some silly things like Donald standing on his head in order to watch a film set at the South Pole, until the narrator dryly suggests just flipping the cartoon over instead, or an Aracuan Bird stepping out of the film inside the film to shake Donald’s hand, and the awesomeness of Donald trying to be a flamingo—and, just as the films end, one of the packages starts to jump and sing and smoke a cigar and then José Carioca pops out and –

No. Wait. Let’s discuss the comparatively normal cartoon shorts that start the film first. The first is a short but sweet story about Pablo, a penguin who simply cannot get warm—the perils of a life in Antarctica—even in his cozy igloo with a large stove. Yes, yes, technically speaking, Antarctica doesn’t really have igloos, but to be fair, Pablo, as it turns out, has postcards and pictures of warm sunny beaches, so maybe he and the other penguins have been collecting pictures of igloos in Alaska and, inspired, decided to model their houses on those. Anyway. Pablo decides that he must, but must, get warm, making increasingly desperate and failed attempts to leave Antarctica as his fellow penguins watch in resignation. Finally—finally—Pablo manages to turn some ice into a boat, and then, when the ice melts, turn his bathtub into a boat, safely landing on an island where he can have sun at last. It’s glorious, with only one minor problem: he misses his fellow penguins.

Possibly because—KINDA HIDDEN MICKEY ALERT—his fellow penguins were playing with a Mickey Mouse sandbucket. (Watch carefully.)

It’s hard not to like a cartoon about penguins, even a cartoon about cheery penguins who get progressively gloomier and gloomier, and my only real complaint about this short is one that Disney animators could not possibly have predicted: it’s narrated by Sterling Holloway, who would later voice Winnie the Pooh in the exact same voice and tones, making me feel that Winnie the Pooh is telling me about penguins and that really, what all of these penguins need is some honey. Distinctly not the point of this short.

The other self-contained short, The Flying Gauchito, plays with a concept rarely used by Disney: an unreliable narrator, who cannot quite remember all of the details of what happened in the past—much to the frustration of the protagonist, his younger self. This raises quite a few questions about the truthfulness of the rest of the tale, in particular the part where the protagonist—a very young gaucho—encounters a flying donkey. Could this donkey really fly, or is the older Gauchito once again confused, misremembering things, or even just making everything up? In any case, Gauchito manages—sorta—to capture the donkey, naming it Burrito. (Not because he’s trying to eat it—this was Disney’s not at all successful attempt at adding the diminutive “ito” to “burro,” the Spanish word for donkey.) The two of them enter a race, unperturbed by the slight problem that, technically, entering a donkey capable of flight into a donkey race is cheating. The other racers are more perturbed, and Gauchito and the flying donkey are raced out of town.

Intentionally or not, both cartoons have a tinge of melancholy to them, along with a sense of “be careful what you wish for.” Pablo finally earns a warm home after all of his hard work, ingenuity, and terror—but finds himself lonely and missing his penguin friends and their happy games on the ice. Gauchito wins the race—only to be an object of hatred. And—almost certainly intentionally—both cartoons have an entirely self-contained story and make sense, unlike the rest of the film.

Speaking of which. So, after the end of the Gauchito short, Donald notices—it’s hard not to—that one of his presents seems about to explode, which it kinda does, revealing José Carioca and a pop-up book. Since his last appearance, José has apparently gained access to a cloning machine or some serious drugs, your choice, and an interest in cross-dressing, which is not the point, and the ability to drag cartoon ducks into pop-up books, Brazil and Mexico.

It’s at this point that things start getting really weird, and I’m not just talking about the cloning, the cross dressing, or the way Donald and José hop in and out of pop-up books and change sizes and have toys chasing them and exploding, or, for that matter, the zany roller coaster train ride they take to Brazil while still inside the pop-up book, which includes a moment where the little cartoon train, following its track, plunges into water and continues underwater for a bit and NOBODY SEEMS TO NOTICE even though the TRAIN WINDOWS ARE ALL OPEN and they should be drowning, and the sudden appearance of the Aracuan Bird from earlier in the film because, er, why not, drawing new tracks that send the individual little train cars rolling off in different directions.

Or why Disney never made a roller coaster based on this little train trip, and if your answer is, because The Three Caballeros is an obscure and problematic film, I will point out that this is the same company that made a popular water flume ride out of Song of the South, so that’s not it.

No, what I’m talking about is what starts at the end of the train trip, when José saunters out, and Donald slides out, of the book. A live action woman saunters through, shaking her hips and selling, er, cookies, and Donald Duck gets turned on. Very turned on, as a portion of his body extends out and I start wondering, not for the last time in this film, what exactly is going on here. The parrot and the duck start to chase the woman—the film shows us that hey, she is carrying cookies, go figure—competing for her, um, cookies, until some live action men show up, also after cookies. At some point, as they continue to dance through a giant book, the cookies are, er, lost, people happily sing “COMER!” Donald realizes that the only person actually getting cookies is the guitar player, José is less bothered, there is a moment with a hat where we should probably ignore the implications, José’s umbrella dances, Donald Duck swings a hammer at a guy dancing with oranges on his head, and I have NO IDEA what any of this is but WOW.

Finally, some more women show up from… I have no idea where, come to think of it—and steal away all of the men from our cookie seller and, if we are to trust the soundtrack, the cookie seller, now pouting in disappointment, makes out with Donald Duck. Things HAPPEN to Donald at this point, and I think you know what I mean, but at this point, the film suddenly remembers that (a) it’s the 1940s and (b) kids might be watching this and suddenly, hammers are banging.

This is the segue into more dancing scenes against an animated background, occasionally interrupted by dancers turning into animated birds, as they do, and then the book literally closes on Brazil and that’s that, with Donald and José barely escaping.

What happens in Mexico? EVEN WEIRDER.

This section introduces Panchito Pistoles, a Mexican rooster with pistols at his side. (I will now dutifully repeat the point that the Spanish here should probably be pistolas, but in a film containing a number of more glaring errors, including all of the mistakes on the map that the little penguin sails by, I’ll let it go.) He and José take Donald on a magic carpet ride through Mexico, which includes a moment where the three of them are so excited to see women in bathing suits on an Acapulco beach that they—the birds—dive bomb down towards them, sending beach umbrellas flying and women running and squeaking, and then Donald dives down again without the magic carpet, squawking “HELLO MY SWEET LITTLE BATHING BEAUTIES” before chasing them around and around the beach, and I have to ask, does Daisy know about any of this? Because if not, I really think someone needs to tell her. Like now. Anyway, a blindfolded Donald ends up kissing José instead which some people have read as gay and which I read as just part of the overall confusion.

Donald is, indeed, so obsessed with women that at one point, his eyes become completely replaced by images of a singer (NOTE: this was not digitally cleaned up in the streaming transfer, forcing viewers to not just look at a duck whose eyes are giant women, but a duck whose eyes are GRAINY giant women). Somewhat later, Donald is just about to kiss a woman only to be interrupted by José and Panchito BURSTING THROUGH HER FACE singing “the three caballeros, the gay caballeros!” Don’t worry: about ten seconds later Donald is, ahem, face down into her folds NOT ENTIRELY A EUPHEMISM and later lands among some dancing cacti which turn into dancing women with some, er, pointed results.

If you’re wondering what the women are thinking about this, well, most of them have firmly pasted on smiles, and seem to be constantly reminding themselves, I need a paycheck, I need a paycheck, I need a paycheck. Or perhaps I’m projecting. Let’s just say they were smiling.

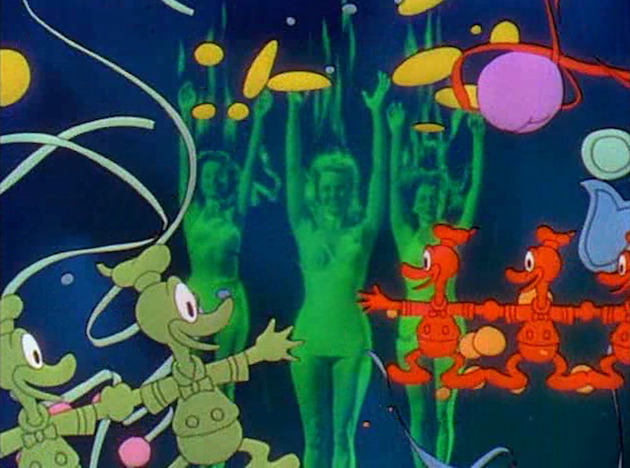

Anyway. The cactus scene was apparently the point where the 1940s New Yorker reviewer completely lost it, wondering what, exactly, the Hays Committee had been thinking when it allowed The Three Caballeros to be released in this format, apparently not comforted by a bit where—possibly as payback for all of this—Donald becomes nothing more than a neon outline of a duck drifting and dancing between other neon outlines. I find myself in full agreement with wondering why, after all the excitement about those (gasp!) bare breasted centaurettes in Fantasia, the Hays Committee let some equally questionable stuff here go, but rather more comforted by the neon dancing scene.

I am leaving out several other bits—the cost saving moment when the camera pans over paintings of Brazil, for instance, or a separate cost saving moment where the camera pans over what I believe are watercolor paintings and some chalk drawings of the Mexican tradition of Posada, the second using a technique developed in Victory Through Air Power that uses camera movements to give the appearance of animation, even when nothing is animated except for a few flickering candle lights here and there.

Also, the amazing bits where Donald Duck temporarily turns into a balloon, and another bit where he turns into a piñata, only to open up into various toys, and the way Panchito hits him, or the final moments, a nonstop barrage of color and movement and transformation and battling toys.

By the time we reached the final bullfighting scene I felt mentally pounded to death.

It all ends, naturally, in fireworks.

Quite a lot of the combined live action/animation, incidentally, was in its own way a cost saving measure. It was accomplished by simply shooting on a soundstage, using the already animated film as a backdrop for actors and dancers, and then filming the entire thing again, allowing Disney to save money by reducing the number of animated cel drawings and the need for complex backgrounds, under the—correct—assumption that the human eye would be drawn to the human dancers and the duck running around between them, not the lack of painted backgrounds. This did result in some occasionally blurry animation work as the cels were filmed twice, but that very blurriness tends to match the overall tone of those sections, and gave Disney some hints about how the company could combine live action and animation in future films. In the end, they mostly went with the idea used for the Donald Duck chasing women on the beach bit—using the film as the background for the animated cels, a technique with occasional clumsiness (more apparent in a couple of upcoming films) but which seemed to have potential.

But for all the weirdness of the combined live action/animated bits, it’s the exuberant animated bits of Donald, José, and Panchito that make the greatest impression. Here, For the first time in several films, the exuberance and energy of the animators who had created Pinocchio and Fantasia emerged again—if in simpler, cheaper form. In fact, if anything, the second half of the film is probably a bit too exuberant and energetic, and often barely coherent, leaping from gag to gag without much seeming point other than exploring how art can transform the characters. But it’s also surreal in all the best ways (the toy sequence, the pop-up books that allow animated ducks to travel to distant places in a single step, the neon dancing) and the worst (animated ducks chasing live women on a beach). Even some cost saving techniques—frames with highly simple backgrounds, or single colored backgrounds—only add to the surreal feel, as well as drawing the eye to the weirdness happening with the animated characters.

It’s….quite something to watch. But what strikes me, watching it now, is how much of it is a deliberate, fierce, almost defiant retreat from reality. Where Saludos Amigos had made an attempt, at least, to give some accurate information about South America, The Three Caballeros offers a vision of South America that—apart from the Christmas bit—makes no claims, even in the bird section, to have much if any bearing on the real world at all. Most of the women Donald interacts with do not exist in the real world, but rather, in pop-up books, or in magical landscapes where a cactus plant can mutate into a dancing woman and then back. The first two shorts offer an almost grim take on the world: struggle to the point of nearly dying to get your dream—only to be lonely and disappointed in the end, or finally find some true magic in your life—only to be driven from your home. Why not, asks the second half of the film, simply walk into a pop-up book, get tortured by a parrot and a rooster, and dance—and dance—and dance?

Why not?

It was also a chance for Disney animators to stretch their creative muscles again and draw with abandon, something they had not been able to do for several films. The sequence where Donald Duck tries to be a flamingo has a free, joyous quality to it that Disney had not managed since Fantasia, and the final sequences are a riot of color and movement that Disney had rarely managed before at all, and would not do again until the age of computer animation. It may—outside of the Christmas bit—lack the delicate beauty and intricacy of the earlier films, and it may often make absolutely no sense, but as a work of art blurring the lines between reality and dream, and as an expression of fierce, damn it all creativity, it’s nearly unmatched in the Disney canon.

The Three Caballeros was released in 1943 to mixed critical opinion and a disappointing box office take, earning just enough to cover its costs—but not enough for Disney to speed up production on the shorts that would eventually be combined into Make Mine Music and Fun and Fancy Free. Disney was, however, later able to repackage the first two shorts as separate cartoons, and successfully released The Three Caballeros five times in theatres and later on home video, allowing Disney to more than recoup the film’s costs. Panchito escaped this film to be a relatively popular character—popular enough, at least, to be the mascot for a store at Disney’s Coronado Springs—if largely without the pistols he first appeared with. The Three Caballeros make regular appearances at the Mexico pavilion at Epcot, although I will once again suggest that adult readers skip them (and the little ride) and instead head straight to the tequila bar.

It was not the success Walt Disney might have wanted—doubtless why Donald Duck would never chase human women with the same, er, intensity again. But The Three Caballeros did help to keep his studio doors open, and also gave him hints of a new direction that the studio might take—live action films with a touch of animation. And it allowed his animators to escape a hellish reality through their art, to unleash a creative energy left largely dormant since their work on Bambi.

Alas, not all of that creative energy made it into the next film.

Make Mine Music, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.